As he suspended his independent presidential campaign and endorsed Donald Trump on Friday, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. talked at length about the “many key issues” on which he claims that he and Trump are aligned. What he did not explain were their profound disagreements in the area that for many years was central to Kennedy’s career and public image: environmental protection.

Kennedy had promised to be “the best environmental president in American history.” For decades, as an attorney and celebrity activist, he urged more vigorous enforcement of federal regulations guaranteeing clean air and water.

Now he joins a campaign whose policies, according to critics, would scale back those regulations and weaken the agencies that uphold them.

His decision has left many of Kennedy’s former allies on environmental causes in shock, even those who had already broken with him over his anti-vaccine views or quixotic presidential bid. Some said the move undid any legacy Kennedy — named one of Time magazine’s “heroes of the planet” in 1999 — could still claim to have in the nation’s environmental movement.

“It’s sad and surreal,” said Michael Brune, a former executive director of the Sierra Club who was arrested alongside Kennedy at the White House in 2013 for protesting the Keystone XL pipeline. “It’s a betrayal of his values and the work that he’s done for most of his career. He’s supporting someone who’s been the most aggressive in terms of trying to undermine our bedrock environmental laws.”

Unlike Republicans who have criticized Trump only to later bend the knee to him, Brune said, Kennedy is — or at least was — separated from him by seemingly insurmountable policy differences.

“In terms of policy issues that people hold dear, I can’t think of another example where a prominent political figure with such a strong record on one issue can go so dramatically and rapidly in the other direction,” Brune said.

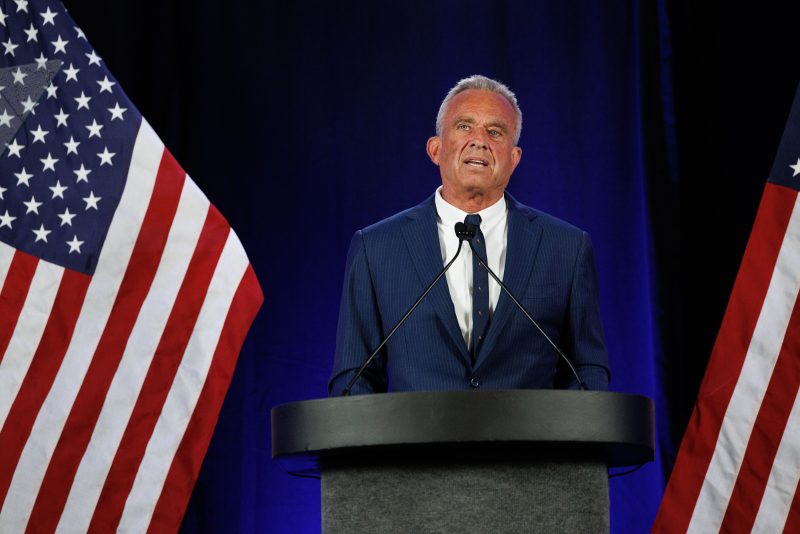

In a speech in Phoenix on Friday announcing the suspension of his campaign in battleground states and his endorsement of Trump, Kennedy seemed to anticipate such criticism, acknowledging that he still had important policy differences with the Republican presidential nominee.

But he said any differences are outweighed by what he called “existential” issues on which he and Trump agree, such as opposing America’s current policy of supporting Ukraine’s defense against Russia’s invasion and “ending the childhood disease epidemic.” Kennedy has for years sown doubts about the safety of childhood vaccines and has promoted debunked theories that link some of those medicines to autism.

“I was a ferocious critic of many of the policies during his first administration. There are still issues and approaches upon which we continue to have very serious differences,” Kennedy said. “But we are aligned with each other on other key issues.”

Just this month, Kennedy was still trying to meet with Vice President Kamala Harris to discuss the possibility of working in her administration if he endorsed her. Unlike Trump, she declined to talk with him.

When it comes to environmental principles, Kennedy’s past rhetoric and activism would seem to align more closely with the Harris-Walz campaign, said Maria Lopez-Nuñez, a partner at Agency, an environmental justice nonprofit and member of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council. She said Harris has been a key figure over the past four years in efforts to extend environmental protections to marginalized people.

“Vice President Harris has been the face of environmental justice for the Biden administration, and we would expect those policies to continue” if she is elected, Lopez-Nuñez said. “Especially when we’re talking about pollution and climate change, I think she’s the only candidate that’s been explicit about that.”

For large portions of his 49-minute speech on Friday, Kennedy — who began running last year as a Democrat — lashed out at the Democratic Party, saying it had prevented him from competing on a level playing field in the primary and criticizing its legal challenges to his independent candidacy in various states.

In a brief phone interview Friday night before he appeared onstage at a rally with Trump, Kennedy said he was “not enthralled with the Democrats’ performance” on environmental issues. Although he had hinted in his speech that his portfolio in a Trump White House could focus on public health, he said that he believed he could also sway environmental policies.

“I would hope to have an influence on how the environment is treated under his administration,” Kennedy said.

During his first term, Trump dramatically rolled back the protections of the Clean Water Act — the landmark 1972 law whose importance Kennedy has emphasized countless times and around which much of his legal work revolved — and sought to slash funding for the Environmental Protection Agency, which Kennedy has frequently assailed for failing to adequately safeguard the American public. Kennedy, who has denounced the country’s reliance on fossil fuels and repeatedly stood among protesters seeking to block construction on oil pipelines, is now part of a campaign that counts “Drill, baby, drill” among its slogans.

Trump apparently overcame some of his own past qualms about his new surrogate’s environmental views. In May, Trump called Kennedy “the dumbest member of the Kennedy Clan” in a post on his Truth Social platform, saying, “He’s a Radical Left Lunatic whose crazy Climate Change views make the Democrat’s Green New Scam look Conservative.”

But for Kennedy — who, unlike Trump, has made environmental issues central to his life’s work — Trump’s past and present policies offer an especially jarring contrast with his own views.

Kennedy starred in a 2011 documentary exposing the ravages of mountaintop-removal coal mining in Appalachia; during his first year in office, Trump halted research on the risks such mining posed to nearby residents. Kennedy often laments regulated industries’ influence over government and attacked former president George W. Bush for appointing men and women who “seem to have entered government service with the express purpose of subverting the agencies they now command.” Trump’s EPA became notorious for politically driven weakening of environmental rules.

“In the Trump administration, among the appointees, they didn’t have anyone who cared about what the science said,” said Andrew Rosenberg, a senior fellow at the Carsey School of Public Policy at the University of New Hampshire and former director of the Center for Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists who has tracked environmental policy across presidential administrations. “To a large extent, it was what powerful business interests wanted.”

Rosenberg said Project 2025, a detailed plan for a potential future Republican administration led by the Heritage Foundation, envisions further reductions to the powers of environmental regulators and cooperation with polluting businesses. (Trump has recently distanced himself from the plan, though some of his former advisers were involved in it.)

Kennedy’s desire to join such an administration, Rosenberg said, is hard to square with his avowed environmental convictions.

“I’m trying to understand the logic,” Rosenberg said. “And I can’t.”